Sotenjuku dojo

Aikido in Egham

Frequently Asked Questions

If you’re thinking about joining our classes, this information might help you decide.

- What is aikido?

- What is aikido training like?

- What do I need to start?

- Is there a beginners’ course?

- How much does it cost?

- How do I join?

- What’s this about insurance?

- Do I need to be fit? Will I get hurt?

- Will I learn to defend myself?

-

You just keep grabbing each other’s wrists!

Why can’t I attack any way I like? - What are the weapons for?

- How do the grades work? How long until I get a black belt?

- What about all the bowing? And the Japanese words?

- How do I contact you?

membership form grading & syllabus

What is aikido?

Aikido is a Japanese defensive martial art founded by Morehei Ueshiba. Although it’s relatively modern (Ueshiba died in 1969), it’s based on much older ju-jutsu techniques and principles from Japanese swordsmanship. The art is characterised by its blending and circular movements, which are used to pin or throw. Unlike judo, it’s not a sport (so you’ll never win anything), and, unlike karate, we don’t kick or punch. You can read our instructor’s views on the art, or try wikipedia’s aikido page.

What is aikido training like?

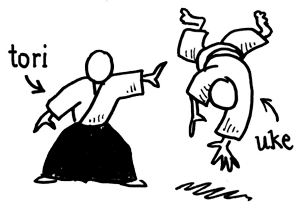

Typically, the instructor shows a technique against a particular attack, and then we pair off and practise that technique, taking it in turns to be the person doing the technique (the tori) and the attacker (the uke) who is being pinned or thrown.

A class always begins with a warm-up comprised mostly of stretches and loosening up. We practise the rolling and falling that is part of the way we learn ukemi, which is the way we "receive" the techniques. It’s because of the characteristic ukemi in aikido that you get to practise full-on — when you’re both proficient, you can apply techniques without holding back because your partner has learnt how to receive those techniques without being injured. When you get the hang of this, even if it’s just fleetingly, it can be exhilarating to do and spectacular to watch.

If you’re about to join us for your first class, it’s only fair to warn you that aikido can also be confusing and frustrating. It’s very subtle, which is why it’s a lot harder than it looks. But that’s precisely why many of us train for years and years and still find it fascinating, difficult, and rewarding. From time to time you will feel exasperated because once again you got your hands round the wrong way or your feet tangled up. Never mind — this never stops, it just gets less frequent.

What do I need to start?

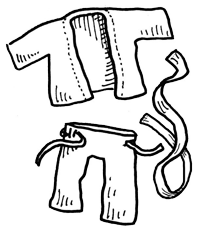

In short: loose clothes.

We usually wear the same white "pyjamas" used for judo (or perhaps karate), called a keikogi. Members who have graded to black belt also wear large pleated "skirts" or hakama. When you’re starting it’s OK to come in loose clothes like jogging pants and a sweatshirt (but if you haven’t got a sweatshirt, a T-shirt will do). We practise barefoot so it’s a good idea to bring flip-flops or sandals to keep your feet clean as you walk to the mat — otherwise use your shoes.

If you decide to join the club and need to buy a new keikogi, we can help with recommendations. Our dojo has an account with Nine Circles, which gives us a discount on most items — ask at class if you want to buy something from them. This 500g keikogi is popular with our members, but if you’re on a budget it’s worth looking on Ebay or in local charity shops.

Aikikai aikido doesn’t use coloured belts to indicate grade, so when you start you’ll be wearing a white belt — we’ve got a bunch of extra white belts so if you get a keikogi without one, just ask and one of us will bring one to the next class to give you.

You must keep your fingernails short (scratching is not part of the syllabus) and keep long hair tied up. Keep your body and your clothes clean, and take any jewellery off before the class starts.

Is there a beginners’ course?

Not specifically, but our instructor Neil's approach to teaching is focussed on the fundamentals anyway. And just so you can be sure you’ll be able to join in, all classes that are good for complete beginners are marked with a heart (when our timetable had three sessions a week, sometimes one of the classes was more advanced).

But actually, since aikido is practised in pairs and everyone adjusts the level and pace of their training depending on the ability of their partner, beginners can just fit in with any normal class. Our instructors modify every class depending on who’s there anyway. One of the amazing things about aikido is that, right from the start, you are in the thick of it, hands-on, with everybody else.

Thinking of starting? Come and join us!

In fact, at the start of 2019 we did run a beginners' course, based on the premise that you can usefully learn the fundamentals in twenty hours of focussed, engaged learning — more information.

How much does it cost?

Your first class is free. After that, we cover the club's costs with monthly payments.

If you join our club, after your first two or three classes you must join the United Kingdom Aikikai. Your membership fee includes your mandatory insurance premium. That money goes straight to the UKA, not to our club.

You do not pay for any gradings until your yudansha (black belt) grading, which — like your membership — is handled by the national UKA anyway.

How do I join?

After a couple of classes, if you want to keep training with us you must join the UKA. To become a member, you need to fill in this membership form (the club name is “Sotenjuku”) and give it to Neil at class, together with your payment (that’s the £35.00 or £27.00 in the table above) (cheques payable to “United Kingdom Aikikai”). This covers your UKA membership for a whole year.

UKA membership form (PDF)

What’s this about insurance?

Everyone routinely practising with us must be covered with third-party insurance. The premium for this is automatically included in your annual UKA membership fee, which is why you must join the UKA once you’ve done your first couple of classes and decided to stay with us.

The third-party insurance protects you if you accidentally injure someone else. In addition to your insurance, all instructors within the UKA have public liability insurance too.

We never run a class without a certified first-aider and a qualified coach being present (four of our members currently hold coaching qualifications recognised by the UKA).

Do I need to be fit? Will I get hurt?

You don’t need great stamina, and even less so physical strength. But an aikido class usually provides a good work-out. Even if the techniques aren’t particularly strenuous, every time you get put down on the mat (and that will happen over and over and over) you have to get up again. You’ll certainly get fitter the more you practise. If you have any doubts about your ability to do physical exercise, consult your doctor first.

Aikido techniques are potentially dangerous, but the padded mats, the system of etiquette, and the cooperative nature of practice are all designed to minimise the risk of injury. Of all the martial arts, aikido is probably the one most concerned with the well-being of the attacker. That’s an odd thing when you first encounter it, but the more you practise the more you realise that it is this which makes the practice so interesting. It’s actually comparatively easy to bash someone about instead of controlling them with aikido, which is what makes practising the art so challenging. Consequently, aikido doesn’t appeal to bullies or to people who are violent or impatient. Occasionally they come, but they don’t stay.

Having said that, practising aikido can sometimes hurt a little — unlike t’ai chi, for example, we do hit the ground and we do get our limbs twisted. We don’t strive to hurt each other, but aikido has a practical element which means that if you are extremely delicate you probably won’t want to come a second time.

Will I learn to defend myself?

Ultimately, aikido is a martial art and if you become competent at it then you may be able to defend yourself from an opportunist attacker. But most people who’ve practised for any significant time will tell you that the confidence and body conditioning that arise from practice are the most practical benefits. Knowing how to fall over safely is handy too.

The fact is that there is no universal method of fast, effective self defence, but if you want to be able to defend yourself, in the long term aikido may help. If you want to learn to fight, it absolutely won’t. Try the competitive martial arts instead.

You just keep grabbing each other’s wrists!

Why can’t I attack any way I like?

Aikido practice is normally conducted with prearranged attacks (technically, what we are doing is rehearsing a form, or kata) because the instructor is demonstrating one particular response, or technique. The attack isn’t a test or a trial, it’s an opportunity to practise and understand how that technique works. All aikido techniques use similar principles of blending and body positioning and you’ll find these are hard enough to learn at the best of times, so it really doesn’t help if your attacker is simultaneously trying fast and unexpected ways of hurting you. The traditional way of allowing the student to focus just on the aiki principles is usually to constrain the attack during practice.

Consequently the attacks are quite formal, and in particular a lot of aikido is practised against grabs to the wrists, forearms, or shoulders. Historically these attacks are sensible ways of preventing a sword being drawn, and, since the movements of aikido are strongly influenced by the sword, these attacks remain at the core of our training method. The relationship between sword-work and empty-handed technique is something that arises again and again in aikido practice. Incidentally, this is why some people regard aikido as a traditional martial art even though it’s relatively modern.

The technical syllabus does include other grabs, chokes, and strikes as well as attacks with weapons or from multiple assailants. Occasionally we practise in a more free-form way, such as not being constrained to one particular technique (jiyu-waza).

What are the weapons for?

Sometimes we practise with wooden weapons — sword (called a bokken) or staff (jo). Although aikido is an unarmed martial art, its movements are based in part on Japanese swordsmanship (kenjutsu) and spear fighting (yarijutsu), because that’s where the founder, Morehei Ueshiba, gained much of his insight. It’s helpful to have some idea of these systems in order to better understand the aikido you’re learning. Part of the syllabus of techniques includes weapon taking, in which uke attacks with a (wooden) sword, staff, or knife (tanto).

In fact, we find the weapons so beneficial both for understanding and rehearsing the movements aikido uses, that sometimes we practice the weapon forms (that means with either wooden sword or wooden staff). Don’t worry if you don’t have a wooden sword or staff handy because the club has spares (although, later, you can choose to buy your own). If you’re a complete beginner, don’t be put off by the word “weapons” — we’re not learning armed combat, we’re practising formal and very clear movements.

How do the grades work? How long until I get a black belt?

We follow the system used at the Aikikai Foundation in Tokyo: students are either mudansha (not dan graded) and wear white belts, or else yudansha (dan graded) and wear black belt and hakama.

The gradings prior to your dan grading are conducted within the club, and really serve as a way for the instructors to monitor and endorse your progress. These grades are called kyu grades. There is no charge for your kyu gradings. The first grade you gain is 6th kyu, then 5th, and so on, until 1st kyu which is the last grade before black belt. Unlike some other martial arts, aikido doesn’t use coloured belts to indicate kyu rank — consequently, it’s not uncommon for someone wearing a white belt to have years of experience.

Dan gradings (the black belt tests) are conducted at the UKA national courses twice a year. It usually takes people around six years before they are ready to take their black belt grading; many people wait longer than that.

Unlike your kyu gradings, if you pass your black belt examination, there is a fee for the Aikikai Foundation in Japan registering your dan grade. This is an international qualification: if you visit aikikai dojos anywhere in the world, your “yudansha book” (it’s like a little passport) will be recognised as valid. Furthermore, it also includes membership of the hombu dojo should you find yourself in Japan (and if you get into aikido that’s not quite as fanciful as it might seem now — several of us, including all our senior instructors, have gone over there to train).

There are no competitions in traditional aikido, so the gradings are not contests. Candidates must not only be familiar with the full range of techniques in the syllabus, but also be able to execute them fluently and correctly under pressure. The only way anyone can do this is by practising for years. Even so, the dan gradings are technically demanding and it’s not uncommon for people to fail. So really we don’t worry too much about gradings — they are not the focus of our practice, the practice itself is.

If you’re doing a grading soon, see our kyu grade syllabus

What about all the bowing? And the Japanese words?

Aikido is a Japanese martial art, and as we are affiliated with the Aikikai Foundation in Tokyo we practise in the traditional way. This isn’t a casual aspect of our practice — from time to time members of our club go over to Japan to train, and our club was given its name by one of the senior instructors there. Furthermore, aikikai clubs all over the world behave in pretty much the same way, so that fact is that learning the etiquette of aikido training is part of learning aikido.

So we bow at the start and end of every class, and before and after every technique. It’s a very clear way of demonstrating that we’re training not fighting, and is an important part of the etiquette which keeps behaviour on the mat predictable, respectful, and safe.

We use Japanese terms for the techniques and attacks. When you start learning aikido, the sooner you can distinguish the techniques and movements you are practising the better, and learning their names is a good way to do this. But — really! — don’t worry too much, because if you just keep training you’ll hear the words often enough that you will eventually pick them up. We have a welcome pack that we’ll give you after you’ve been on the mat, which helps explain some of the vocabulary and etiquette — after all, we do know some of this can seen a little bewildering when you first start.

How do I contact you?

See our contact details.

Images: CC-BY-SA Beholder www.fudebakudo.com/aikido